March seems to be the favoured month for monetary policy regime shifts in Norway. In March 2001 inflation targeting was formalized, with a target of 2.5 percent inflation annually. 2 March 2018 he Norwegian government announced a new inflation target of 2 percent for Norges Bank to pursue.

There were two immediate responses. The Norwegian foreign exchange rate immediately appreciated, apparently because of anticipations about higher policy interest rates. At the same time, Norges Bank, played down the importance of the government’s decision, saying, in a press release: … “the new regulation will not result in significant changes in the conduct of monetary policy”. Nevertheless, helped by the government’s decision, the focus now will swing back to the conventional aspects of monetary policy, to the use of the interest rate in activity regulation, and to the precarious relationship between the bank’s interest rate path and the future rates of inflation.

Meanwhile, Norwegians’ appetite for loans has continued to increase. Debt service costs are currently at high levels, even with the low interest rate. It is unlikely that there is much scope for interest rate increases before there will be negative consequences for private consumption, and for net demand for housing.

On the other hand, it is will be difficult to continue flying the flag of inflation targeting without starting to weight the inflation-gap “back into” the interest rate response function. Maybe not with the same coefficient as before the financial crisis though? Using NAM (Norwegian Aggregate Model), we have simulated some possible effects of the new inflation target, assuming that the Bank is half as aggressive in its interest rate setting as it was before the financial crisis. For simplicity, we assume that new policy response comes into operation after the summer (of course it can happen earlier, but perhaps more likely, a little later).

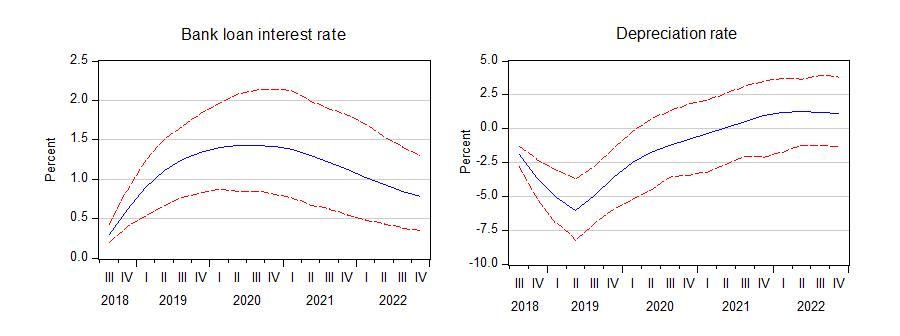

The graph to the left shows that the interest rate on bank loans (ie the rate that matters for households) may increase by 1.5 percentage points (on expectation). The dashed lines indicate the upper and lower bounds of a 95 % confidence interval. Clearly, the effect on the interest rate can become lower (as the interval indicates), but also higher, which may be bad news for the robustness of continued demand impulses to the economy.

Another interesting variable to look at is the exchange rate. The graph to the right in the figure shows the estimated appreciation, which in the model is due to the increase in the domestic interest rates. An increased international value of the krone will please Norwegian holyday makers abroad, but may at the same time frustrate export and import competing firms.